Navigating the Complex World of Fresh and Saltwater Management and Law

In an era of climate change and increasing water scarcity, understanding water policy has never been more crucial. From California's ongoing drought to the East Coast's flood-drought cycles, water challenges are reshaping our world. But did you know that water laws change drastically at the shoreline? Or that 70-80% of water rights in Western states are tied up in agriculture?

In this eye-opening episode of Liquid Assets, host Ravi Kurani sits down with Robin Craig, an esteemed professor from USC, to dive deep into the intricate world of water policy. Craig, a leading expert in environmental law and author of "Re-envisioning the Anthropocene Ocean," breaks down the complex landscape of water management, from freshwater allocation to ocean conservation.

Whether you're a policy maker, environmental enthusiast, or simply a concerned citizen, this episode offers invaluable insights into one of the most pressing issues of our time. Discover how water policy shapes everything from your daily life to global ecosystems, and learn about the cutting-edge solutions being developed to address our water challenges.

Don't miss this opportunity to expand your understanding of water policy and its far-reaching impacts. Tune in to Liquid Assets for an enlightening conversation that's sure to change how you view this vital resource.

What you'll hear in this episode:

- The stark differences between freshwater and saltwater management

- How water laws vary between dry and wet regions

- The water-energy-food nexus and its policy implications

- Climate resilience in water law and its regional challenges

- The future of ocean management and innovative solutions

Listen On:

Watch the interview:

Meet Robin

Robin Craig is a distinguished professor at the University of Southern California, bringing a wealth of expertise in environmental law, water policy, and climate change adaptation. With a unique background that bridges science and law, Robin's journey from chemistry major to renowned environmental legal scholar offers a fresh perspective on some of the most pressing issues of our time.

Robin's passion for solving real-world problems through law and policy makes her a leading voice in the field. Her work on climate adaptation law, in particular, stands out for its practical approach to complex environmental challenges. With over a decade of experience in this niche, Robin brings invaluable insights to the conversation on water management and climate resilience.

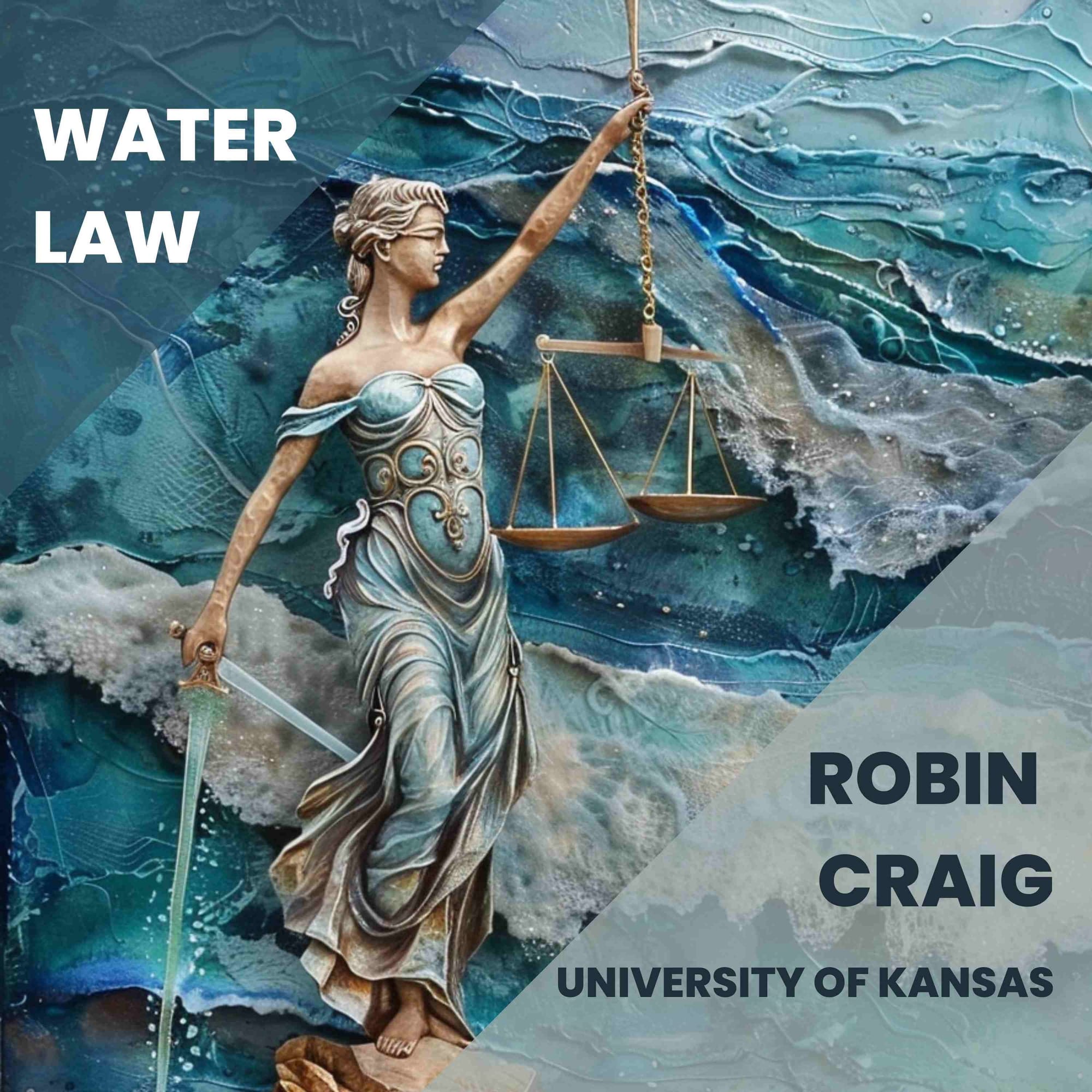

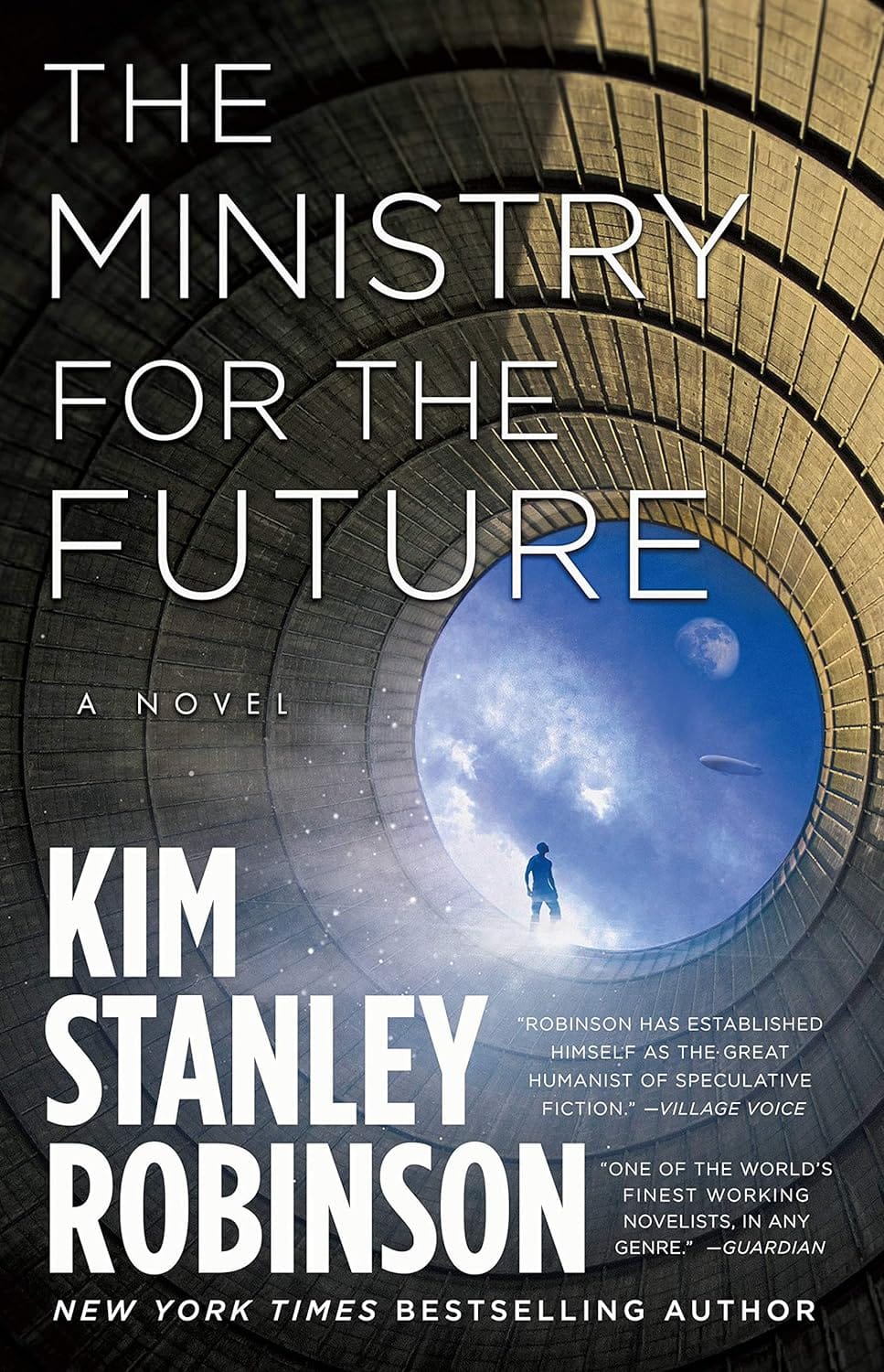

The Book, Movie, or Show

In this episode, Robin Craig highly recommends "Ministry for the Future" by Kim Stanley Robinson. This science fiction novel offers a profoundly realistic view of climate change impacts while providing a hopeful vision for the future. Robin praises the book for its well-researched content and its ability to envision practical solutions to climate challenges.

As a bonus, Robin introduces listeners to "Solarpunk," a new science fiction genre focused on envisioning positive future scenarios and the paths to achieve them. These recommendations reflect Robin's belief in the power of forward-thinking narratives to inspire real-world solutions to environmental challenges.

Contains affiliate Amazon links.

Transcript

00:00

Ravi Kurani

Welcome to Liquid Assets. I'm your host, Ravi Kurani. Liquid Assets is a podcast where we talk about the intersection of business, policy, and technology, all as it looks at water.

00:10

Ravi Kurani

Today, we have a remarkable guest for you, Robin Craig, an esteemed professor from USC. In this episode, you'll uncover some eye opening issues and insights. Robin discusses the critical distinctions between fresh water and saltwater management and how these impact everything from drinking water to marine ecosystems. For instance, did you know that water laws drastically change at the shoreline? Tune in at minute five to learn more. We also dive into the implications of water laws in dry versus wet regions. Ever wonder why California struggles with water rights while the east coast deals with flooding and drought cycles? Robin breaks it down starting at minute 16. And if you're curious about the future, don't miss our discussion on climate resilience and innovative solutions for our oceans. From the impact of ocean acidification to the promise offshore wind energy, Robin shares cutting edge research and practical advice.

01:09

Ravi Kurani

Head over to minute 32 for these forward thinking ideas. Robin is a passionate advocate for rethinking our relationship with water and the oceans. And this episode is packed with knowledge that could change how you view these vital resources. Stay tuned for an enlightening conversation that's sure to broaden your understanding of water policy and its impact on our world. Let's go ahead and jump in.

01:35

Ravi Kurani

Robin, how are you doing today?

01:37

Robin Craig

I'm doing fine, Ravi. Thank you for having me.

01:40

Ravi Kurani

Yeah, of course. It's a pleasure. Before we hit the record button, I know you were going back and forth on what we should cover on today's podcast, and you raise an interesting point of there's a distinction between fresh water and how this entire global system works. Maybe you can just start by unpacking the rules of the road, if I may, around water and water policy.

02:06

Robin Craig

All right. It's a pretty complex area of law. One basic division is between freshwater and salt water. And in many countries, including the United States, there is a very emphatic change of rules and policies at the shoreline. And we go from freshwater management to ocean water management. So for fresh water, you're usually worried about two things, water quality, making sure water stays fairly clean, which in the United States is handled through the Clean Water act and state implementations of similar statutes and allocation of water. So who gets to take out the fresh water and use it for various things like irrigation or drinking, or a municipality wanting to supply drinking water to its citizens? All of those things are governed by different policies. There's a final distinction between surface water and groundwater. So there are places that manage those very differently.

03:11

Robin Craig

California is one example. Arizona is another example. Historically, groundwater, because it was considered occult and mysterious, and we didn't know quite where it was. If you could find it, you could grab it. And that was known as the rule of capture. As we got better at finding groundwater, that turned out not to be a great rule because people take a lot of groundwater when they know how to find it. Most places have gone away from the rule of capture and used something else. Surface water in the United States and around the world depends on hydrogeographic realities, what kind of policies you're going to come up with.

03:48

Robin Craig

So if you live in some place that's hot and dry, chances are you have some version of prior appropriation where the first person to take water from a surface water source and apply it to what in the United States is known as a beneficial use. But basically, anything good you would want to use water for has some priority, because hot, dry places recognize that it's likely on a regular basis that there won't be enough water to go around. So that's the law in most of the american west. It's the law in some hot and dry places in Africa, countries in Africa, and it just helps apportion water where you have not enough. If you live someplace wet that has a lot of water, most of the year, you probably do some sort of a sharing of water.

04:42

Robin Craig

In the United States, it tends to be based on reasonable use. There are other ways of sharing water. Sometimes it's on a community level. Sometimes it's on a person level, property owner level. There are different ways of sharing water. But if you've got enough to go around, you have some sort of sharing doctrine in place. So that's a basic overview. When it comes to the ocean, there's all sorts of things going on. There's people who are worried about energy development, and other people who are worried about marine mammals, and other people who are worried about endangered ecosystems like coral reefs and kelps. Kelp forests. Yeah. Once you get in the ocean, there's a lot of people trying to do a lot of things at the same time.

05:28

Ravi Kurani

Wow, that's definitely a lot to unpack. So if I'm just going to regurgitate that back to you. At the top of this kind of food chain, there is fresh and saltwater alongside fresh water. What you talked about, there's water quality and then the allocation of water, right? Who gets to use the water? And then basically, is it safe to use in that particular way? And then I guess double clicking into that, you have the surface water and groundwater standpoint, and then a demarcation of whether you're in a dry area or a wet area, which kind of then really boils down into beneficial use. Prior appropriation to reasonable use. If you're in a wet area and then splitting it up there, I want to get a little bit into what is beneficial use versus reasonable use in this dry, wet area.

06:13

Ravi Kurani

I'm sure the audience is wondering, do we, in California, we're in a dry area, do we focus on growing plants and vegetables because we're a big agrarian state, whereas somewhere in the east coast you might be able to share more of the water around the reasonable use. Can you define what that reasonable use versus beneficial use means?

06:33

Robin Craig

Yeah. So beneficial use is basically, are you doing something that the government thinks is a good thing to do with water? Classically, both east and west, the highest use of water is for domestic use. Drinking water, bathing water, a small garden, maybe in some places, stock watering, all of that. Beyond that, beneficial use and reasonable use are related, but not in the west. What you're using the water for definesen what the scope of your water, right. Is, how much water you get and when you can use it. If you're using it for irrigation, you're typically going to have a lot of water, but only during the irrigation season, whatever that might be. For where you are in the crop you're going. Reasonable use is more of a sharing concept. That means you're not taking more than your fair share.

07:25

Robin Craig

And if you have a lot of in eastern United States, go with riparianism, which means if you own property next to a river or a stream, you get your fair share of that river or stream. And so reasonable use is if there are ten of you and it's a big river, you can take more than if there are 20 of you, and it's a small stream, you get what's reasonable given how many people there are trying to use the same amount of water.

07:54

Ravi Kurani

Got it. Okay. That makes a ton of sense. And then if we move into the saltwater arena, can we unpack that a little bit? Because I know you also wrote a book on re envisioning the anthropocene ocean, which I want to go to after this, but maybe we can get the lay of the land again on the saltwater ocean side.

08:12

Robin Craig

Okay. Yeah, on the saltwater. So not as many people want to take and use salt water. If you do, there are some power plants that use saltwater for cooling water, for example, or if you've got a desalination plant, then you're going to be under the same regime as whatever state controls that water. So if you're in the west coast state, it'll be prior appropriation. If it's an east coast state, you'll be water sharing, reasonable use kind of standard. But there's a lot going on in the oceans. Like I said, it gets pretty complicated pretty fast because there are a lot of different agencies regulating a lot of different things going on in the water. So if you're.

08:52

Robin Craig

The ocean in the United States is basically federal states, through an act called the Submerged Lands act, have a lot of control over the first 3 miles, but that's because Congress gave it back to them after the Supreme Court said the oceans are basically federal. So you've got a federal overlay to everything. So if you want to build a dock or you want to put a jetty or a marina into the ocean, you're probably going to be dealing with the US Army Corps of Engineers, which is the agency in charge of structures. If you want to be drilling for offshore oil and gas, as is prominent in the Gulf, and we have a few of those here in California, then you're dealing with the Bureau of Ocean Energy Management. If you want to fish, you're dealing with NOAA and the regional Fishery Management councils.

09:50

Robin Craig

If you're going to do something that interferes with marine mammals and you're doing it with NOAA or the US Fish and Wildlife Service, depending on which marine mammal it is. If you want to do aquaculture, you're dealing with a whole host of agencies, but you might run afoul of the state's coastal zone Management act. Like I said, it gets very complicated, very fast. And if you're doing something that pollutes the waters, you're dealing with the US Environmental Protection Agency and maybe the state, depending on how close to shore you are. So it gets very complicated very fast, and a lot of different agencies have different authorities in the ocean.

10:30

Ravi Kurani

And you just mentioned right now that the US has federally jurisdiction up to, you said, 3 miles off of the coastline.

10:39

Robin Craig

No states were given back jurisdiction up to 3 miles off the coastline. The federal government, under international law, can regulate up to 200 nautical miles offshore.

10:50

Ravi Kurani

I see.

10:51

Robin Craig

Okay.

10:52

Ravi Kurani

And if we go through the gamut of things as a pareto of what people are doing in the ocean, more than less is the bulk of it like fishing and drilling or what kind of are we, what are we doing in the ocean?

11:08

Robin Craig

There's a lot of fishing. So that's a big one. There's a lot of building of things, marinas, docks, ports, a lot of transportation. People forget that a lot of how much transportation maybe now they remember because of COVID and the problems we have, but a lot of transportation goes by. Ocean ports and transportation lanes are important. Offshore drilling gets a lot of attention, but if you're not in the Gulf of Mexico, there's actually not that much of it going on. There's a lot in the Gulf of Mexico. There's a little bit off of California, there's a little bit off of Alaska, but otherwise, not as much of that. Fishing, transportation, and building things are the three big activities in the ocean. Beyond that, there's environmental protection and things like marine protected areas, national marine sanctuaries, marine national monuments, state versions of the same thing.

12:06

Robin Craig

So there's the protective side of it as well. Increasingly, there's aquaculture and offshore wind. Those are new developments in the offshore aquaculture has been going on in some states for centuries, but commercial scale big offshore wind and commercial scale big offshore aquaculture are new to a lot of states, but those are both growing industries that we'll see more of in the future.

12:37

Ravi Kurani

Really interesting. Let's jump into your book that you also just recently published around, re envisioning the Anthropocene Ocean. Can you talk through the big idea there? What are your thoughts?

12:48

Robin Craig

Yeah. My co editor, Jeffrey McCarthy, and I, before COVID got a grant to try and have an upbeat interdisciplinary conference, which we had on new visions of the ocean and the goal of the book from a variety of disciplines, to rethink our relationship to humans, relationship to and our dependence upon the ocean and how the ocean creates life, supports life, creates community, ties us all together. And that was a conference. We had some great scientists. We had national geographic explorers. We had people who work in the blue humanities, which usually goes through english departments. We had some lawyers. We had psychologists. We had a whole bunch of people, just like I said, thinking about how do we envision a better future for how we treat the ocean? How do we take it seriously?

13:51

Robin Craig

We tend to assume that nothing human beings can do, and this is written into a lot of the laws, too, that it's very hard for human beings to damage the ocean. But we know from fisheries, and now we know because of the climate change impacts on the ocean, that's not true. And so re envisioning, revaluing the ocean were the overall arching themes of the chapter.

14:19

Ravi Kurani

And if you were to summarize that into a bullet point or a handful of bullet points. What is the re envisioning? Where are we coming from? Which I think you obviously talked about with folks not taking the ocean seriously, the fact that humans are not able to impact the ocean, what does it look like today? What does this re envisioning look like?

14:39

Robin Craig

It starts with acknowledging that we are dependent on the ocean, that it's a huge part of food security, that it's a huge part of our climate, it's a huge part of our weather. We are dependent on the ocean. It's a huge part of our international transportation and commerce. Second is to respect it, to realize that the ocean needs to be left alone sometimes, to have space, to adapt, to have time, to adapt to increasing heat and changing chemistry because of ocean acidification. And third is to celebrate our relationship to the ocean and recognize that if we don't get that's eventually going to be the worst part of climate change. But on the upside, could really bring us the new forms of energy and food that can help us transition as we are dealing with climate change's impacts and others arenas.

15:42

Ravi Kurani

And if you were to maybe split apart what regular citizens could do versus, obviously, governments and states, if for people in the audience listening out, there is anything that a citizen can do, a quote unquote regular person, the biggest thing.

15:58

Robin Craig

A citizen can do is be careful about what you eat. Fishing, like I said, is a huge impact on the ocean. There's very good evidence that human fishing has taken out most of the large predators from the ocean, which has affected food webs all the way down. It impacts the resilience of the remaining ocean ecosystems and ocean marine critters to adapt to climate change. And there are some very good lists. The Monterey Bay Aquarium, for example, is a very good list of things that are okay to eat from the ocean and things that aren't. And we still consume, in some places, parts of the world, 20% of people's protein comes from the ocean. Even in the United States, it's often close to 10% of your protein comes from the ocean. So just be careful about what you're eating.

16:55

Ravi Kurani

Got it? Okay, we'll definitely have to put the Monterey Bay aquarium link on your show notes when we launch this live. Definitely, yeah. Talking about food, I actually interviewed one of your colleagues, which is how we got introduced, Sean Hyatt, who has an episode earlier in this podcast. I want to shift a little bit to the water energy food nexus. He had a lot of things to say about how policy falls on various parts of the line of whether it's water policy, or you're making energy from water and then it falls under energy policy. And you said you would be the perfect person to double click into that. So can you maybe start up at the 50,000 foot level, and then we can go ahead and dig deep into the water energy food nexus?

17:39

Robin Craig

Yes. So this is one of the places where reality and what law and policy say don't always align correctly, because almost all forms of energy depend on water for something. For example, if you have a traditional coal fired power plant or nuclear power plant, it's going to need cooling water to keep it cool enough, but you have to have enough water around that's cold enough to allow that to happen. Various forms of solar take water. Manufacturing of solar equipment takes water. Obviously, hydropower is dependent on water. Energy is dependent on water. Water is dependent on energy. Water is heavy. We move a lot of water around. Even if you're thinking just in a municipal system, you have to be pumping that water.

18:28

Robin Craig

If you're in a place like California, where we're pumping water from the Colorado river across the bottom of the state, we're pumping water from the northern part of the state to the southern part of the state. That takes a lot of energy. It's something like 10% of California's total energy budget just goes to moving water around. It's a lot of energy. And then in the midst of all that is food. So we need water to grow food. We need water as part of the food. We ship a lot of water out of the country or from place to place in the form of food, both for ourselves and animals. We need energy to grow the food. If you think of all the fertilizers that are based on fossil fuels and oil, we need to transport it around. So all of that is intermixed.

19:19

Robin Craig

And as policy decisions, what we do with water has very little to do with what our energy policy otherwise is. Decisions we make about energy policy often don't take account of, hey, where's the water going to come from? And then all of this in terms of food. We leave food production in the United States to the open market. But that doesn't mean we're necessarily growing the right things in the right places, or that we have sufficient water to grow them where we're growing them, or that all of it will be actually used as food. We waste a tremendous amount of food in the United States and waste the water and the energy that went into that in the process. So it's all interconnected, and our policies and laws governing each one don't really take that into account.

20:16

Ravi Kurani

And so what will your suggestion be, since the policy around water, energy and food are siloed, of how to fix that?

20:26

Robin Craig

It's a tough. It's a tough go. The Department of Energy, about a decade and a half ago came out with a report, realizing that everything it wanted to do with energy policy was dependent on there being water. And the water was controlled by the various states, so it couldn't really command what to do with the water. Personally, I think we could start, and this flies in the face of traditions and agriculture, but we could start by being a little more rational about our agriculture and thinking about agriculture maybe on more of a national scale than an individual farm scale. So I'll give you some concrete examples. In the west, because of the way the west was settled and because of prior appropriation, about 70% to 80% of water rights in each of the western states is tied up in agriculture.

21:21

Robin Craig

And there's no real incentive in the law for agriculture to modernize its water practices, because prior appropriation is also use it or lose it. For example, if you put in drip irrigation instead of unlined ditches, you'll use a lot less water. But that water, under most states laws, just reverts to the state and is given away to someone else. We could come up with policies that would both incentivize and provide money for transitioning to less water use in agriculture, while at the same time providing grants to farmers to update and giving them a stake in the water they save by letting them mark it. About half some states have experimented with that, but we, at the same time, we can also think about what we're growing.

22:14

Robin Craig

Counterintuitively, hydroponic farming often uses less water as well as less land, and you're often growing more valuable crops. So again, with some financial assistance and incentives to various farmers to try and change over, that would be a great way to do it. And it would save, free up possibly some water for the environment or for growing cities in ways that could be quite helpful. But we can also think about what we're growing, where we send a lot of water to other countries in the form of alfalfa to feed a beef industry that has a lot of impacts beyond health, public health. We sometimes are growing rice in the desert. Rice is an intensely water needful crops. Thinking about where we're growing, what like you said, this flies in the face of the free market that usually dominates our agriculture.

23:11

Robin Craig

But the federal government also gives out a lot of money and a lot of incentives in the form of the farm bill. It's not like it's ever been a completely free market. And we could fairly easily start by using some of the farm bill incentives to not incentivize, say, soybeans and feed corn, but instead incentivize some other conversions of agriculture.

23:42

Ravi Kurani

Really interesting. Yeah, I've heard that a few times that we grow flood irrigated rice in land that otherwise would not have water available. And we're also exporting a lot of alfalfa for other countries beef exports, which is funny, because I remember reading a book on how food security was the main point of World War Two from the US's standpoint, and we're exporting a lot of that from. So from just from like a security standpoint, seems a little bit anthetical when you look at food policy.

24:14

Robin Craig

Yeah.

24:18

Ravi Kurani

Sorry. Go ahead.

24:18

Robin Craig

Oh, go ahead.

24:22

Ravi Kurani

I was just going to shift a little bit to climate change and water law. You had mentioned a few times around ocean acidification, the fact that groundwater is moving around, and it's hard to pinpoint where it is with the government actually having such a hard time in just understanding the interconnectedness of water, energy and food, which almost seems like a surface level understanding. How do you get folks in policy to understand climate resilience in water law? And what does that mean? I'd like to dig deep just the way that we did on the water energy food nexus.

24:57

Robin Craig

Climate resilience in water law generally means making sure that you still have water for the uses you want, despite climate change, and that I'll stick with the United States. It has different implications depending on where you are and what you're used to. But in the United States, the hot and dry west is projected to get hotter and drier, and as a result, less rainfall, less water in the rivers. This has become a major talking point for the Colorado river, which seven different states share and is governed by what's known as the law of the river. Starting from 1922 on how to divide the Colorado river up, the division assumes that there's on average about 16.5 million acre feet per year flowing in the Colorado river.

25:51

Robin Craig

And so an acre foot is the amount of water it takes to cover an acre of land with 1ft of water. So it's a huge amount of water. But that was never true. First of all, the 1922 compact came up with that idea on the basis of some of the wettest years the Colorado river has ever experienced. But with climate change, depending on what period of the last couple decades, you look at the Colorado river is down to something like 13 million acre feet, 11 million acre feet. Some people even say 10 million acre feet per year. And so we're at a shortage of what everybody expects of somewhere between three and 6.5 million acre feet per year. And so climate resilience is figuring out what do we do about that? Our storage systems on the Colorado river have been greatly depleted.

26:45

Robin Craig

Lake Powell and Lake Mead. Chances that we'll build them back to full are slim. It would take many years of higher than average rain, and that's not what we've been seeing. So what do we do about that? Do we get more efficient about our water use? Do we start doing what love Las Vegas did long ago? Incentivizing people, not having lawns, not having a lot of grass on golf courses, hotels, reuse every drop of water? Do we put in water recycling like we have here in Orange county, in California? Do we try to drop demand? Do we get more efficient with how we use water? Do we look at that 70% to 80% that's going to agriculture and decide, yeah, we need to get serious about how we do agriculture in the west. All that is climate resilience related to water.

27:41

Robin Craig

Now, in the east of the United States, they're used to having plenty of water. And so all of their law, but also all of their hard infrastructure, is designed to deal with flood. And that's fine when that's your big risk. But if you've been paying attention to the Mississippi or to the southeast, they're now in a regime where they're fluctuating between extreme floods one year and extreme drought the next. And we're facing situations where the Mississippi doesn't have enough water in it for barges to get up the Mississippi. And that's still an important use of the Mississippi river. Climate resilience in the east means more of learning how to change on a dime between a drought year and a flood year, and maybe putting in some more infrastructure that can help with drought.

28:38

Robin Craig

Having legal regimes and operating manuals for dams and reservoirs that try to anticipate what the next year or next couple of years will be. Is this a year you want to release water from reservoirs? Because we think it's going to be a flood year next year. Is this a year you want to hoard every drop you can? Because we think next year is going to be drought year. That's actually a much harder transition. The west was built to deal with hot and dry, and it's just a matter of dealing with it getting worse. Whereas I sympathize with people in the east, because climate resilience means, like I said, being able to change on a dime between years that may be diametrically opposite ends of the water cycle.

29:29

Ravi Kurani

That's such an interesting comparison you made, because I think when we think about California, Arizona, Texas, Nevada, it seems like a lot of the general public will think about water problems in the drought that California has. But an interesting point that you mentioned of the southeast having these fluctuations between flood years and drought years. And yeah, really interesting implication there. I want to take a bit of a left turn into what drives you as Robin, what's your background? Why did you get into this? Why are you passionate about this?

30:02

Robin Craig

I've always loved both the humanities side of things and the science side of things. So I actually started out as a chem major, found out I had a tolerance for 4 hours of lab a week, and went into science writing for a while. But I found a way to combine the love of science and the love of the more social humanity side of things in environmental law. And what drives me for about the last 1314 years has been trying to figure out the law and policy side of climate adaptation. When climate change was recognized as a legal problem scientifically, most of the focus initially was on climate change mitigation. How do we reduce our greenhouse gas emissions? How do we pull greenhouse gases back out of the atmosphere?

30:56

Robin Craig

That has a scientific component, has a technological component, and as a legal component, but the legal component is really not that difficult. And I know that sounds heretical to say it's politically difficult, but legally, how to draft emission standards, how to set a limit, that's a fairly easy to statute to draft once the world decides what it wants the limit to be and how to divvy it up. And of course, those politics have been haunting us for at least four decades now. Politically difficult, but legally easy adaptation, on the other hand, because it is particular to place, and what's going on in that place is a much more difficult law and policy issue, in particular because there's also a lot of equity and justice issues that come up when you're trying to think about adaptation.

31:52

Robin Craig

Who has to move, who gets the water, who gets the food, who has to bear the expense of doing whatever it is you need to do to adapt. And so I find that a much more fascinating area of law. And of course, water is at the heart of almost anything. We're going to have to adapt to changing food supplies, ensuring food security, making sure humans have just the basic amount of water they need to survive, making sure that water stays clean, making sure the oceans are still functional despite increasing temperatures and decreasing ph. And that's just a much more challenging and hence more interesting legal and policy problem to be thinking about. And it's not a one size fits all solution.

32:39

Robin Craig

Every place is going to need a slightly different package of adaptation strategies and adaptation laws in order to stay resilient to climate change.

32:52

Ravi Kurani

If you think back to you morphing from your chemistry side to the policy side, hindsight 2020, obviously, is there a defining time where you were like, oh, this particular moment is why I wanted to move from one side to the other.

33:09

Robin Craig

It was actually a slower progression. But when I was in graduate school, I realized part of what I really wanted was to be in a subject where it had to connect up with reality and helping people at certain points. And that's one reason I ended up in law, is because whatever you want to theorize about what should work or what we could do, sooner or later, you have to test it out in reality and see if it does work or if this does actually help people. And that was the part that very much appealed to me, the problem solving mentality and outlook that characterizes a lot of environmental law and climate adaptation law in particular.

34:00

Ravi Kurani

Really interesting. And if you go back and think about, do we have the execution capacity? Like you just said, making the laws are probably the easiest part about this. Do we have the technological and the execution capacity to actually put those laws into effect? Once we actually think about what the emission standards should be, et cetera.

34:26

Robin Craig

I think it depends on who you ask and what technology you like the best. Carbon sequestration is something that a lot of people talk about. I don't think we're quite up to commercial scale testability, and that depends on having someplace to put the carbon dioxide, which, depending on where you are, you may or may not have reservoirs available. So we're getting there. We're getting there, probably gotten there on electric vehicles, but we need now the infrastructure to support the electric vehicles and to not having them run off of coal fired power plant electricity. We're getting there with solar's close to being competitive, price wise, as other forms of energy. We're getting there with wind energy.

35:15

Robin Craig

I'm excited to see some of the offshore wind come online, because if that's done, it could both generate a lot of energy and support the environment, believe it or not, and be cost effective ways of generating some clean energy. Like I said, I think we're getting there on a lot of technological fronts. We're not quite all the way there. So people who want to actively remove carbon dioxide from the atmosphere, the best technology we have is still plants. So plants do it better than anything humans have come up with so far. And I think some of the more effective solutions for a lot of reasons, are to grow the plants up and then sequester the plant material underground or other places so the carbon stays sequestered. Sometimes low tech is better tech, and that seems to be one area where that's.

36:10

Robin Craig

I think there's the fact that people are looking at a variety of things simultaneously, I think is a good thing. Whether we will do all of this as fast as we should be doing all of it remains to be seen if we're going to go all renewable energy. There are huge infrastructure issues with that. There are water issues with that. We don't have the grid we need to be doing that. We don't have the transmission lines we need to be doing that. We don't necessarily have water in the right places at the right time to be doing some of that. I have a friend who, part of what she does as a lawyer is help get the temporary water that new renewable energy projects need just to get built and get going. So there are lawyers working on that practical side of it, too.

37:00

Robin Craig

But it's going to be a massive transformation and all hands on deck, and we seem to be getting there. So that's me in my positive mode.

37:12

Ravi Kurani

That does sound definitely promising. I ask everybody the same question on the podcast and it's is there a book, a tv show or a movie that has had a profound impact or changed your worldview, either entirely or on the world of water?

37:31

Robin Craig

I'm. I think Ministry for the Future by Kim Stanley Robinson has been one of the recent reads that, in short, gave me hope. It's a profoundly realistic book about what climate change means, and if Kim Stanley Robinson's work at all. He does amazing research for all of the science fiction books he writes, but he found a way through, and he found a way through that rings true to the extent there's a bunch of us that do climate adaptation law that read that book, and every once in a while when something happens in the world, we text each other and say ministry for the future just happened. So I highly recommend it as a read or a listen. It's got a great audiobook too, because it doesn't flinch from the realities of what climate change might mean. But like I said, envisions a path forward.

38:33

Robin Craig

And that's what we need more of is people who are in detail, not dreamily, not unrealistically, but really thinking about what the way forward would be. That was part of what re envisioning the Anthropocene Ocean was about. There's also a new genre, science fiction, I just. Just got turned on to. It's called Solarpunk, but again, it's focus is Solarpunk. Yeah. Figuring out. Figuring out the path through, figuring out what it looks like on the other side and how we got there in a positive way. And I think that's what we need more of right now, is people who are thinking through what should the other side look like and how do we get there from here.

39:20

Ravi Kurani

I love that. Awesome. You'll have to put a ministry of the future and Solarpunk on your show notes as well. But Robin, thank you so much for coming on liquid assets. For all those of you out there, you can listen to liquid assets wherever you listen to your podcast. Be that on YouTube, Google Podcasts, Apple, or Spotify, you can find us at Liquidassets CC. And Robin, thanks again for coming on the pod.

39:45

Robin Craig

All right, thank you, Ravi. Happy to be here.

39:47

Ravi Kurani

And for all of those of you out there, if you want to listen to liquid assets, you can find us at Liquidassets Cc or anywhere else you get your podcasts or on YouTube today.